DIPLOMA, 1986, VISUAL ARTS

ALUMNI DISCOVERY INITIATIVE INTERVIEW BY JENNIE ALVES, JULY 2015 (UPDATED BY NH JUNE 2018)

JENNIE ALVES: What can you remember of the community atmosphere of ACAD?

NELSON HENRICKS: My experience was that the school was pretty wide open. You could do whatever you wanted to do. The thing that made ACAD really dynamic was that everybody in third and fourth year had studios on site. It made it a really interesting place to be: the school was very active and very lively. This activity continued into the night as well. A lot of people stayed and worked at the school in the evenings. I worked a lot in the evenings and would usually stay fairly late. I know many students stayed overnight: some people would sleep there, some people were even kind of living there. There was a lot of partying happening as well, but not just partying: a lot of creative stuff was happening after 5:00pm or 6:00pm. Bands were formed. Conversations happened. Collaborations started.

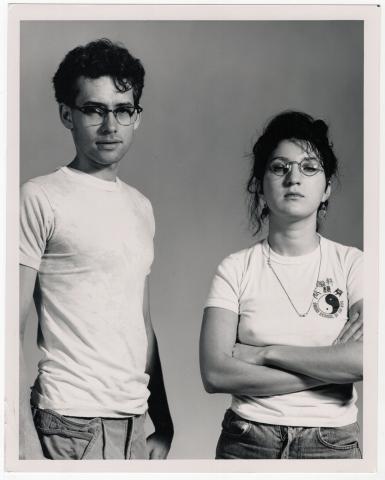

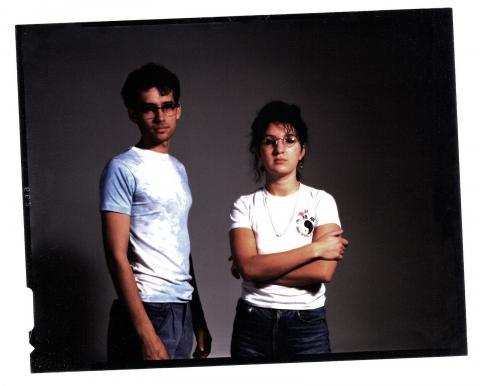

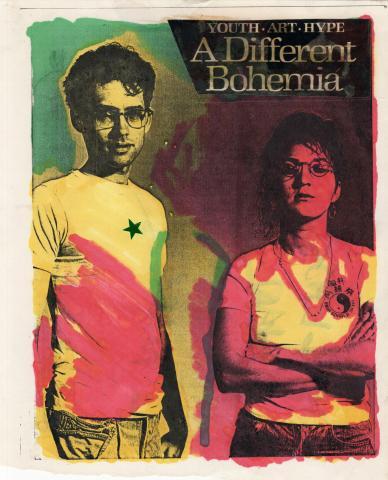

I was working in the second floor drawing studios. We sort of set up house there. There were maybe twelve of us in that space. I remember myself and Colleen Kerr started a collective called “A Different Bohemia”. One night we threw a painting party. We repainted the entry hallway to our studio with DayGlo paint, installed a black light, and held this massive art event. We were later reprimanded for it. The head of our department sent us a letter and threatened to withhold all the final grades for third and fourth year drawing students. People were pretty upset. People were crying. So a few weeks later we threw another art party and painted the space white again. We treated the studio environment like it belonged to us. As if it was our home, in a way.

I remember it was also easy to access equipment and services. At ACAD, if I wanted a Super 8 film camera, I’d just walk downstairs to the equipment depot and say to Chuck Hughes, “I want a Super 8 camera”, and he would give it to me. I disappeared to New York with one for a week and no one raised an eyebrow.

Students, and contact I made with other students, were the most important part of the ACAD community for me. You tend look at your colleagues––whether you’re a student or an artist––and think, “Wow that person is really far thinking. That’s really out there. I wonder how they got there?” One of the pieces I remember seeing at the Student Gallery was by David P. Smith and Geoff Hunter I think. They had taken a white enamel bowl and put it on the floor, and had hung a paring knife on the wall above it. A piece of white string connected the knife to the bowl. They had cut a picture of Picasso out of a fashion magazine, and put it in the bottom of the bowl, and then pissed in the bowl. The whole show was full of works like that––it was just wild. This would’ve been 1985 or so. Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ was 1987. It just sort of seemed like a potent combination of materials and images.

A Different Bohemia Collective, Nelson Henricks and Colleen Kerr (Photos: Ken Flett)

A Different Bohemia Collective, Nelson Henricks and Colleen Kerr (Photos: Ken Flett)

JA: What can you remember of your experience with instructors at ACAD?

NH: I had so many great instructors at ACAD: Blake Senini, Gord Ferguson, Wally May, Stuart Parker, Alan Dunning, Wendy Toogood, and Derek Besant. I remember asking Mary Scott about her process, how she made work, and if she had a studio or not. She just said, “I don’t have a studio. I just make stuff in my bedroom.” That was really liberating for me. There is this expectation that you have a studio, that art is made in a certain way, and that an artist behaves in a particular manner. Not having a studio doesn’t necessarily have to be an impediment towards making work. Maybe making art is something that is integrated into your life. It can happen in a domestic space, and it doesn’t need to occur in isolation, somewhere else.

Just having the opportunity to interact with professors informally was nice. I remember in fourth year my professor was Ian Baxter. We really socialized a lot with Ian and his wife Louise, who was also really sweet. Practically every week one of the students would organize a potluck supper, and Ian and Louise would always show up. I bumped into both of them at the Toronto Art Fair last year. They haven’t changed.

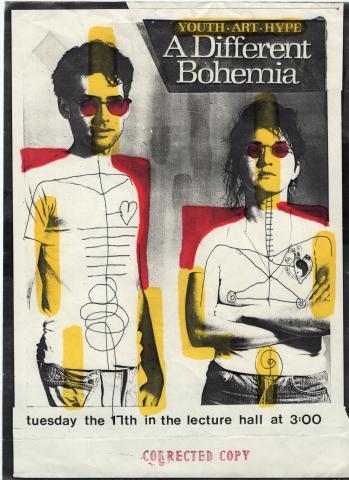

Posters for A Different Bohemia performance event (Credit: Henricks & Kerr)

Posters for A Different Bohemia performance event (Credit: Henricks & Kerr)

JA: Why do you think that creativity matters in the big picture?

NH: What my experience has been––observing my own students––is that not everyone ends up working as an artist. Often times they end up in different fields, or they work in different creative sectors. A lot of my former students are working in music, for some reason. If we think about what creativity is––lateral thinking or problem solving abilities––that kind of thinking is really useful in any field. I think it’s a really good skill to build. So the idea that creativity is important is very powerful. The ability to invent and to think differently: to come up with new knowledge. No matter what field you’re working in, basic problem solving ability gives you a real advantage.

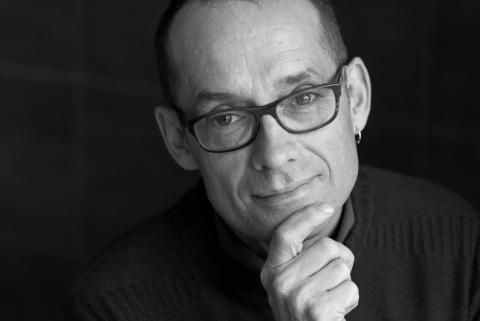

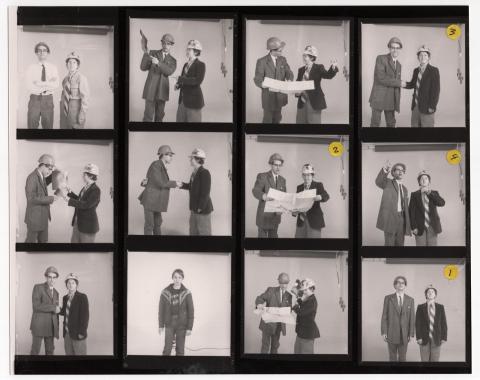

Nelson Henricks and Colleen Kerr (Photo: Cathy Schick)

JA: What is unique about video over other art forms?

NH: What attracted me to video initially was the ability to combine text, sound, and images. Does that make video unique? I don’t know. It seems there are probably other forms that allow you to do that, especially cinema, though the differences between film and video have been conflated over the past two decades. Maybe people your age really don’t see them as distinct media. Reading theory has caused me to question this need to define essential characteristics for certain media. I think that this is more of a modernist approach. Instead of thinking about media in terms of what they are, maybe it’s more interesting to think of what they do, and how they perform.

Something that video does that other forms don’t do is it allows you to explore the nature of reality. This is something that Tom Sherman has written about: the immediacy of video. You can film something and then play it back. This ability to capture bits of reality and play them back, or manipulate them, makes video an excellent philosophical instrument––I think that’s the term Sherman uses. It’s a tool for thinking through, or thinking about, reality.

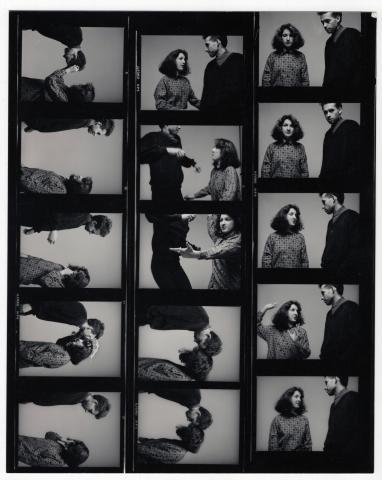

Promotional photos for A Different Bohemia’s “A Short Passage” event (Photo: Ken Flett)

Promotional photos for A Different Bohemia’s “A Short Passage” event (Photo: Ken Flett)

JA: Film and video?

NH: There was a material difference that separated the two. Film was shot on film, and video was shot on videotape. Two different communities arose around these media. The distinctions became about use of the medium, rather than modernist essential characteristics that are based on materiality. The idea of immediacy was very important to video in the early years.

What I’m interested in is encoding things into the work that can be decoded by privileged audience members. A simple example: I recently used a deaf signer in a work and I decided not to subtitle what they are saying. To me, it was more interesting that someone who was hearing impaired could come to the work, look at it, and have a different kind of experience than somebody who didn’t speak ASL. Maybe in that moment of the work they were privileged, and had a certain access to the work that hearing enabled people wouldn’t have, a reading of the work that could occur on different levels. Sometimes the way I construct the work is about privileging a certain kind of spectator: building something into the work that only they can access.

I was doing some work around synesthesia and I happened to meet this guy who has synesthesia (he associates colours with letters). It was interesting to me that he was the ideal audience member for the work. It was fun to talk to him about his experience. But these kinds of encounters don’t happen frequently. And sometimes the elements encoded inside the work are pretty subtle.

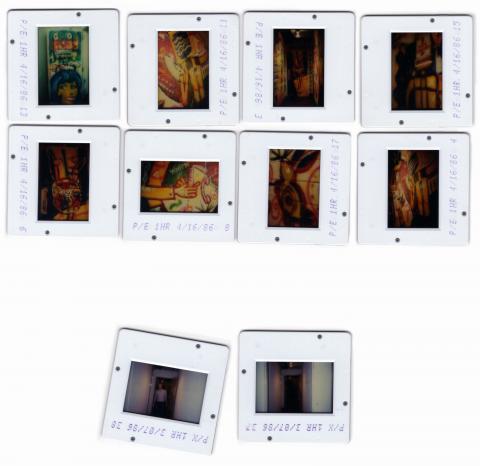

Poster for A Different Bohemia’s “A Short Passage” (Photo: Ken Flett)

JA: You are currently doing your PhD in Research-Creation at the Université du Québec à Montreal. For someone who doesn't quite know what that means, could you describe what it looks like?

NH: In practical terms, a research-creation degree is 50% studio practice and 50% writing. So the four-channel video installation “A Lecture on Art” (2015) was the studio component, the studio based research. The writing component was a 150-page thesis, which is now written, defended, and done. The center point of my research focused on making sound visible, modalities of making sound visible. I’m using synesthesia as a generative strategy for art making, but also as a tool for thinking: to open up or unpack this idea of making sound visible, of making sound tangible.

I think every artist has certain themes or ideas that they are continually coming back to: specific questions they’re trying to answer through their work, problems they’re trying to solve. A large part of the PhD process is helping you to identify those problems and questions, the repeating motifs or the repeating themes that are coming back in your work. When you’re in art school, you have to write a lot of artist statements. The research-creation PhD is a similar sort of process: figuring out what your work is about, what your preoccupations are. So I’ve noticed that for about ten years I’ve been concerned with questions of translation, or the transposition of information. Maybe it does come from my own experiences of synesthesia. But beyond that, I think many artists or writers use metaphors and allegories as our stock and trade: they’re ways of representing ideas. So my research relates to art making and creativity in broader terms as well.

Slide documentation of the A Different Bohemia’s “Short Passage” installation while it was up, and once it was erased. (Photos: Nelson Henricks)

JA: Does experience matter to the creative process?

NH: I think it does. There are some artists who gain a real technical mastery as they go along. They develop confidence in their technical abilities. Maybe it’s like a good jazz musician: you can improvise a lot easier and you have a lot more confidence because you have all this experience backing it up. Again, if you make art for many years, you see certain themes or certain problems reoccurring over and over again. You learn to identify what they are and define your preoccupations as an artist. In that sense, I think experience matters conceptually as well. I think that’s part of what we’re trying to teach people in art school: to try and recognize those ideas, those reoccurring themes that will become sort of guideposts for the rest of your practice. For no matter how long you’ll be working, you’ll keep coming back to them.