VISUAL ARTS ALUMNA, 1959

ALUMNI DISCOVERY INITIATIVE INTERVIEW BY ARKATYIIS MILLER, 2015

Karen Moller in her Paris studio writing the first edition of her memoir, Technicolor Dreamin', in 2007. Image courtesy of Karen Moller.

During her years spent attending art school in Calgary, when the Alberta College of Art + Design was then simply known as the art department of Calgary’s technical institute or “the tech”, Karen Moller took off hitchhiking to San Francisco where she began her lifelong journey in art and fashion.

Her fashion career flourished when she opened the first textile design studio in London in 1969 and culminated with the creation Trend Union in Paris in 1985, a design consulting and forecasting firm which TIME magazine named as, “One of the World's Most Influential Fashion Futurists”. In 2007 she wrote her memoir, Technicolor Dreamin’, a personal and critical history of the 1960’s and 70’s counterculture. Technicolor Dreamin’ was first published in Canada 2007, later re-edited as In Her Own Fashion in the U.S.A., then translated in Spain in 2014 as Sonando en Tecnicolor, and in 2017 it was re-edited in England as Technicolor Dreamin’ In her Own Fashion.

Purchase link http://amzn.eu/fjUe8Oj

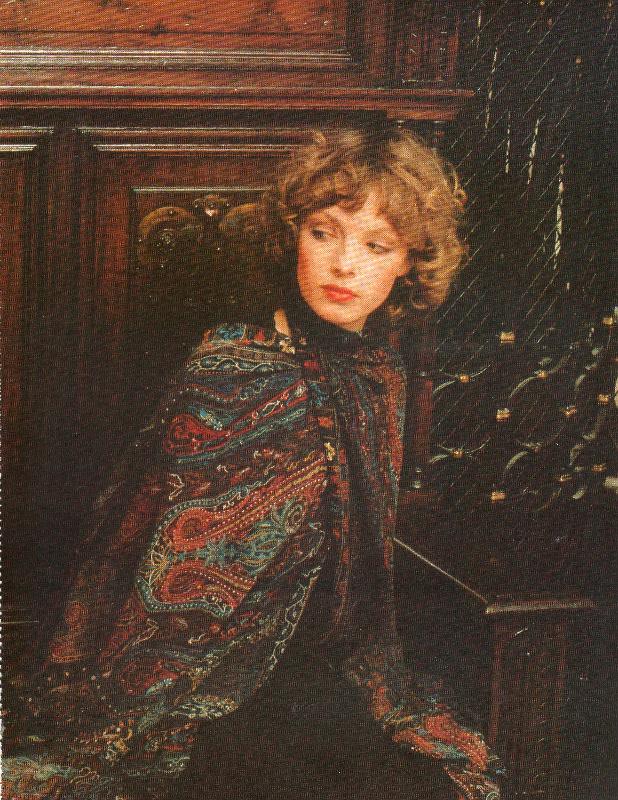

1966 London, Karen Moller's fashion design on the cover of Fashion Magazine

Through ACAD’s Alumni Discovery Initiative, Arkatyiis Miller had the opportunity to chat with Karen, and help us learn a little bit more about her time as an art student, as well as get a glimpse into some of the adventures and accomplishments she now has under her belt.

1. When did you graduate? I didn’t exactly graduate as I left before the end of 1959 for San Francisco. That was about the time the art department of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art was being split into the Alberta College of Art (ACA), and the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT).

2. What was your major? Do you continue to work in this area or did you change areas of interest? Fine Art Major. In my first year as a student there were only about 40 students in the first year, with many of them girls. By the second year, of the 20 or so girls only 3 remained; the others had failed or dropped out.

In San Francisco I worked in a restaurant to earn travel money for my trip to Paris. Paris was overwhelming. In the sixties my friends were artists – most became famous: Yves Klein, Joseph Beuys, Robert Filliou, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and Eva Appelli. Even then we felt gallery and museum systems had become corrupted by commercial interests (which is even worse today. I remember thinking to myself, “do I really want to be part of this corrupt (art) world sucking up to people just to sell my work?” After a year, overwhelmed by the enormous number of art actives around me I decided to hitch hike to Southern Spain to think things over. To make money to live on, I designed furniture and fabrics and decorated people’s homes. After designing a boutique in Torremolinos, the shop owner said, “I like your style. Why don’t you design me a few garments?” In Spain with dressmakers on every corner that was an easy job.

I moved to England in 1962, the beginning of the free and easy times that led to the hippie period. As no one would hire me without a design diploma I borrowed money from friends and opened a boutique of my own clothes designs. Because of my art background and my active participation in a design area the pre-dip department of the Leicester College of Art invited me to teach one day a week. It was the moment when art education changed in England and the course was very similar to that taught by Stan Perrot in my years the Alberta College of Art (an obvious spin off from Hans Hoffman course in New York). I continued teaching that one-day a week for 7 years (a job I loved) while developing my studio for textile designs. One day it became so successful I could no longer spare the time.

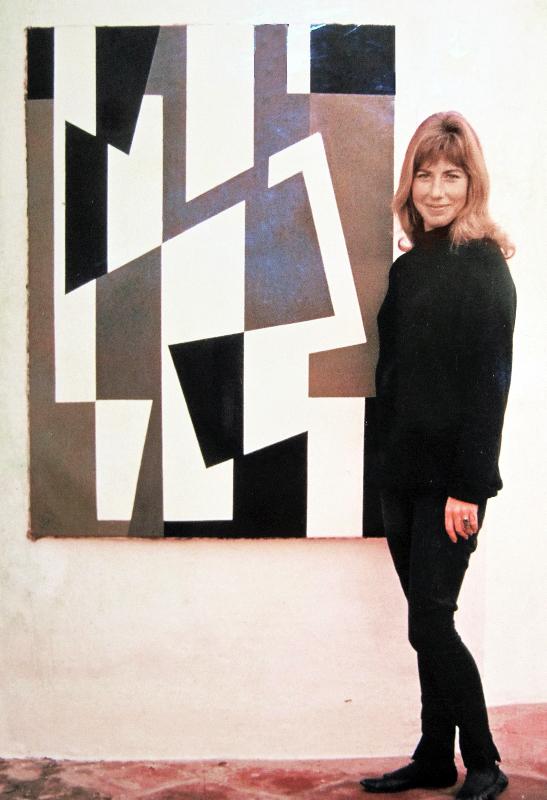

Karen Moller stands beside one of her paintings at her studio in Spain, in 1960. Image courtesy of Moller.

3. A lot of graduates use the ACAD degree as a creative stepping stone. How did your education at ACAD direct your career?

Art school was where I first felt I belonged. “Art is a way of healing.” If you haven’t suffered, you perhaps don’t have drive to overcome barriers. Ken Sturdy, one of my favorite professors made me feel it was ok to be a rebel, to live my life as I chose and not accept the conditions imposed on women. He filled my head with dreams when he told me about his days as an existentialist in Paris. That’s what great professors do; expand the hopes and dreams of students. It was also the comradeship between us and our professors: we hung out with them, we were invited to tea on Sunday, and we partied and drank together in the beer parlors and on picnics. It was great and created a lot of fond memories.

I left the art school with the feeling I could do anything I put my mind to. In 1969 opened the first textile design studio in England, previously designs were all made in Italy and France. After a trip to Intersstoff the German’s fashion fair, where my clients introduced me to the various important fabric producers I realized the potential for my designs worldwide. Italy buyers were vey enthusiastic and open and virtually bought all my designs on each trip– the problem was to get them to pay. Once I’d replenished my supply of designs I made trips to New York, which began to make me rich. I moved my studio to Paris in 1976 and in 1985 I created Trend Union, named by TIME magazine as ‘One of the world's most influential fashion futurists'. Fashion futurists tell the designs what the fashion will be in two years time so they can prepare their collections.

All this brought me me to writing my memoir in 2007—a personal and critical history of the 1960’s and 70’s counterculture.Technicolor Dreamin’ was published in Canada, later reedited as In Her Own Fashion in the U.S.A., then translated in Spain in 2014 as Sonando en Tecnicolor, and in England in 2017 reedited as Technicolor Dreamin’ In her Own Fashion.

Moving Canal, 1962, for an exhibition of Young Contemporaries in London.

4. What would you like to be recognized for?

Only the top fashion houses are remembered. Other areas of the industry fade once one is no longer active. I would like to be remembered for writing books, notably Technicolor Dreamin’ where I tried to capture the art and cultural essence of the sixties–seventy’s with its original and innovative fashions, music, art, literature, and radical changes in freedom and censorship. Most important was how our activities helped to bring more equality to women.

5. Given your experience, what advice would you give a student when it comes to establishing a creative business?

Passion and originality. That’s all you need and a belief that what you are doing is worth doing. It’s important to have a unique style and voice as well. That goes for all fields. People call Andy Warhol’s art decorative but it’s not true. Andy told me that selling is what it is all about, which it is, along as that does not interfere with one’s vision of one’s own creations. As long as the selling only comes after the creation. He said art was merchandise and mocked the old idea of the committed geniuses holding out against a corrupt art market. “It’s a sucker’s game. We all know much of the avant-garde wants to be in.” Personally I don’t think there is anything wrong with making money, but it’s an artist’s artistic achievements, not the financial success that measures an artist.

Art students should develop their minds as well as their art. Reading philosophy and great works of literature and intellectual conversations help nourish creation. Because I lived on the route to the art school Stan Perrot would pick me up on my way there in the mornings. Those few minutes I had to talk to him about books and art was food for a hungry mind.

What insights did your four (or one, two, three, five, six) years at ACAD give you when looking at things? I was born a rebel. It was months before my professors believed I was serious about becoming an artist. Don’t forget it was a time that people believed the only destiny of a woman was to marry and have children. My father refused to help me as he felt education was wasted on women.

Calgary was very lively in those days with the Coste House, lots of Jazz clubs, theaters and a cinema club that showed foreign films. With the flooding into Canada of cultivated Hungarians after the Hungarian revolution many cultural centers opened. The Java Shop (our coffee shop) transported a bit of Europe to Canada. It served great cappuccinos and was the place to hangout for like-minded individuals interested in alternative culture.

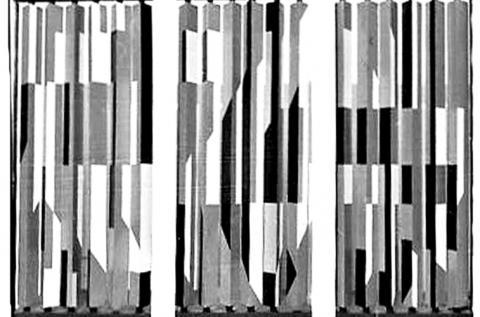

1970 Karen Moller's textile design for Yves Saint Laurent.

What obstacles did you encounter and how did you overcome them ? Inspired by Kerouac's book, On the Road, I took off hitchhiking to San Francisco where I met Ferlinghetti and the beatnik poets. For me the Beats had no gender; they were rebels doing what I wanted to do. I was pretty dumb not to realize I could never be part of that brotherhood nor liberated like those guys. It was a comradeship of men, with Kerouac and the Beats swaggering off to the next adventure, leaving their pregnant girlfriends to look after real life. Women remained collateral, just as they had always been, simply possessions of men. The Beats altered that to ‘the ideal woman doesn’t belong to a man she belonged to any man who wants her.’ That was my first obstacle.

Although I had worked in a restaurant in San Francisco and saved money the second obstacle was finding work in Paris to keep me from starvation and to pay for my art classes. I sold encyclopedias to Americans and became the handy man for artists, some of them are now famous artists. The Poetry and Art Events were very educational and exciting as were the 1960s: ecological, sexual, feminist and political protests in London which not only helped liberalize our society but changed the way we think and the way we dress. Apart from teaching one day a week at the Leicester College of Art I opened a boutique selling my hippie fashion designs, which I later wholesaled to Carnaby Street and Kings Road, and throughout the world. In 1969, I established the first textile design studio in London and after winning awards and gaining international recognition, in 1976 I moved my studio to Paris. Shortly thereafter I created Trend Union which I’ve described already as being named by TIME magazine as ‘One of the world's most influential fashion futurists'.

What do you feel is the role of ACAD and our alumni in shaping our cultural and economic prosperity?

I feel it is really important to focus on cultural activities. Having culture clubs, cinema clubs, which open the eyes of students to the outside world. I think ACAD should encourage students to gain experience by “getting out into the world and meeting other artists.” Almost every movement of importance in art came about from artists meeting like minded artists. Art and culture is often undervalued, so it is under paid and occasionally when someone’s art it is taken up, usually because it becomes a worthwhile financial investment it is then over paid. All part of art’s sorry history. I would like to add, that I never focused on making money, my aim was always to make enough money to keep on doing what I wanted to do. And to my surprise, doing what I wanted to do led to my success.

Looking back at our #ACAD creativity matters campaign, why do you think that creativity matters in the big picture? Creativity is the base of anything. You can make anything and everything creative. Read Robert Filliou or Joseph Beuys on that subject: they are both fascinating.

Where does art fit into your future? Art was and is my life and always will be.